Mazan Gudu, a community in Gabasawasa Local Government Area, Kano State, with a population of over 10,000 residents, is increasingly facing serious threats due to excessive sand mining activities that have left inhabitants grappling with severe social and environmental consequences.

The mining operations have caused extensive destruction of farmlands and traditional cattle routes, forcing herders to pass through cultivated fields. This disruption has intensified tensions and fuelled recurring conflicts between farmers and herders within the community.

A SolaceBase investigation has uncovered major actors involved in the sand mining activities, including Gerawa Global Engineering Company, Cosgrove Infrastructural Limited, alongside several other foreign and local firms that have descended on what was once a peaceful settlement.

Beyond environmental damage, the abandoned mining sites have also emerged as security flashpoints, particularly at night. Residents now live in constant fear as criminals, including those from neighbouring communities, reportedly use the sites as hideouts to store stolen items and rustled cattle.

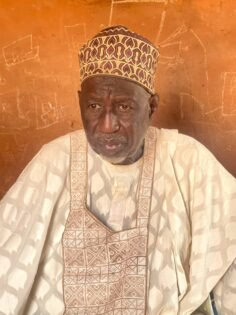

Despite repeated complaints lodged with relevant stakeholders, including local government authorities and the head of the community, Alhaji Yusuf Abdullahi, no concrete action has been taken. Community members alleged that this inaction is linked to gratification received by some officials from the mining companies.

Meeting miners, protests in vain, as cattle routes are destroyed

Farmer-herder conflict has long been a traumatizing reality affecting many communities across the country, claiming lives, leaving widows, and orphaning children who continue to grieve the loss of their loved ones.

In Mazan Gudu, residents have watched helplessly as sand mining operations threaten the community’s safety and livelihoods.

To protect their community from further harm, a delegation of locals met with the miners, urging them to preserve the link roads connecting Mazan Gudu to neighbouring communities, as well as the traditional cattle routes.

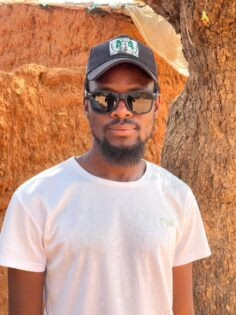

Tasi’u Idris recounted that the community met with the miners twice, appealing for at least the routes and grazing paths to be spared. “We pleaded with them to leave the link routes and our farmlands intact, as well as the cattle routes, but it was all in vain,” he said.

Another resident, Rislanu Yusuf, explained that despite involving both the village and district heads, as well as relevant security agencies, the menace remained beyond their control.

He added, “Initially, mining activities were taking place almost six kilometres away from our homes, on the outskirts of the community. Now, it is barely half a kilometre from our houses, making us increasingly fearful and worried.”

The destruction of the link routes has had tragic consequences. Yusuf recalled a recent incident in which a pregnant woman suffered severe bleeding while trying to navigate the damaged roads, dying before she could reach the hospital, along with her unborn child.

When engagement with the miners failed, concerned citizens staged protests against what they described as the unjust destruction of their community. However, these demonstrations yielded no meaningful results.

Peace disrupted, crops and lives at risk

Mazan Gudu is predominantly inhabited by Hausa and Fulani communities, including nomadic Fulani who, for decades, lived in relative peace. However, the rise of sand mining activities in the area has become a source of chaos, straining relationships and fueling conflict.

Daha Abubakar, a local farmer, recounted bitterly how some Fulani herders now navigate through his farmland with their cattle, destroying crops.

He blamed the miners for deliberately excavating and obliterating historic cattle routes, forcing herders to trample cultivated lands and sparking unrest.

“There was a time when they entered my farmland to find their way home and destroyed nearly the entire field, leaving only a little behind,” Abubakar said.

“Such destruction by both settled and nomadic Fulani has happened countless times. Sometimes they pass at night. In the morning, you would just see the loss and grief. It is even an understatement to say it is unbearable.”

Abubakar added that he has tried to retaliate or intervene whenever possible, but much of the damage occurs when he is absent, particularly at night. “I leave them, the miners and the Fulani, to God,” he said.

Rabi’u Bago, another farmer, shared a similar experience.

He recalled a confrontation that erupted after herders trooped through his farmland, destroying crops while returning from grazing their cattle.

“I saw them coming and warned them not to enter my farm. But after I left, news of the destruction reached me. I rushed back, and a confrontation ensued, sparking fresh conflict,” he said.

Abdullahi Habu, another local farmer, explained that some herders travel long distances only to find the traditional cattle routes destroyed upon arrival in Mazan Gudu. With no other option, they are forced to navigate through farmland, causing further damage.

“Sometimes, even while working on your field, you suddenly see a Fulani man walking through your crops, causing destruction. These incidents continue to create chaos in our community,” Habu said.

Armed confrontation averted as traditional leader intervenes

The Deputy Head of the Fulani in the community, Yakubu Galadima, recounted a harrowing incident in which a confrontation between farmers and herders nearly turned violent.

He said the conflict erupted after some Fulani herders allegedly allowed their cattle to stray into a farm and destroy crops.

The farm owner lodged a complaint, prompting him to intervene.

“I was at home when someone rushed to take me on a motorcycle to the scene to restore peace. By the time I arrived, the parties were already quarrelling and exchanging insults,” he said.

According to him, the situation quickly escalated. “They were holding weapons. The Fulani men angrily approached the farmer, insulting him and attempting to attack him. I stood in the middle, speaking to them and urging them to stop.”

Galadima explained that his authority as a traditional Fulani leader helped calm the tension.

“You know, Fulani people, when a Fulani leader speaks, they listen. That was how I stopped them and later resolved the matter,” he said.

He added that, as of the time of the interview, several reconciliation efforts between farmers and herders were still pending before him, but he had delayed attending to them because of the interview.

‘Mining, conflict are forcing us out,’ Fulani leader laments

Yakubu further added that the escalating mining activities and recurring conflicts are gradually pushing Fulani families out of a community they have lived in for years.

According to him, the destruction of traditional cattle routes linking them to grazing areas and government-designated reserves has left many herders stranded and increasingly unwelcome.

“The cattle routes connecting us to different grazing areas have been destroyed. The places where we used to feed our cattle are no longer accessible, making the community almost irrelevant to us,” he said.

Galadima explained that during the rainy season, many Fulani families are forced to leave Mazan Gudu entirely to prevent their cattle from straying into farmlands and triggering fresh disputes.

“Once the rainy season begins, we have no option but to take our cattle and leave until it ends, because we fear misunderstandings with farmers,” he said.

He added that even after the rains, tensions persist. “We are hopeless. Even when we return after the rainy season, if farmers have not harvested their crops, we are still in trouble,” he said.

While acknowledging that some disputes involve nomadic herders who fail to properly control their cattle, he stressed that the destruction of cattle routes has worsened the situation.

“We are always settling disputes between farmers and herders. Some of the problems involve nomadic Fulani who sometimes leave their cattle unattended. But this issue has worried us for a long time. Government should secure the cattle routes and the forests so Fulani can move and feed their cattle peacefully,” he said.

Chaos, fear as Fulani man killed around mining site

The village of Mazan Gudu was thrown into pandemonium after the body of a Fulani man was discovered in the outskirts of the community, near the active sand mining site. While the cause of his death remains unclear, many residents believe it may be linked to a suspected conflict.

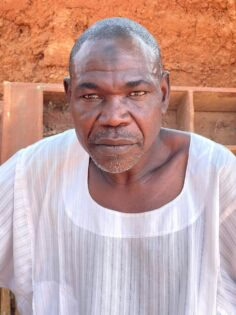

A respected community elder, Malam Abdullahi Habu, described the mining site as increasingly dangerous and recounted the harrowing tale of the Fulani man’s death.

He warned, “The continuation of mining activities in this community will generate even more serious tension. It could lead to weapon attacks, stabbings, and killings between Fulani herders and farmers.”

Malam Habu recalled that even before the escalation of mining, violent incidents had occurred.

“Long ago, when mining activities were less severe, a Fulani man was attacked and killed in the area,” he said.

Although internal disputes over cattle routes and farmlands between the parties have been ongoing, Malam Habu noted that the exact reason behind the killing, as well as those responsible, has yet to be identified.

Mining pits turned hideouts, community security threatened

Tension has risen in Mazan Gudu as residents claim that abandoned mining pits have become hideouts for criminal activities, attracting outsiders who use the area to conceal stolen cattle and sheep. Locals describe the situation as increasingly worrisome.

Malam Abdullahi Habu explained that rustled cows are often kept in the large holes created by mining, saying, “Such incidents have occurred countless times since the beginning of the mining.”

He added that people from neighbouring communities sometimes come to Mazan Gudu in search of their missing cattle, a development that has tarnished the community’s reputation and created opportunities for hoodlums.

Alhaji Yusuf Kawu noted that even their own goats and sheep are at risk. “If they are stolen, they would be kept in the mining pits, where no one dares to enter for fear of their safety. The place has also become a den for criminals,” he said.

He further explained, “The large mining pit has become a disturbing site with serious security concerns. It stores stolen cows, goats, and sheep from even distant communities. Its vastness is such that anyone entering can easily get disoriented.”

Another resident, Daha Sulaiman, described the dangers of the area, saying, “We only pass through during the morning until around 5:00 in the evening. Any time after that, following the rough paths becomes too dangerous for our safety.”

Compliance at a Cost: Peace and livelihoods undermined

SolaceBase uncovered an alleged financial arrangement between the miners and a local government official under the Directorate of Personnel Management of the secretariat, identified as Hamza Lawan.

According to sources, revenue from the miners is collected, allowing them to continue operations despite the environmental damage and destruction of traditional cattle routes.

The revenue officer, Malam Maikudi, reportedly collects payments from the miners on behalf of the local government. These payments are sometimes made per trip, at the end of the month, or annually, depending on the terms of the agreement.

Major mining companies admitted to providing certain sums of money to the local government official overseeing the mining activities.

Despite the devastating consequences for the community, the official reportedly remained silent, prioritizing financial gain over environmental protection and community welfare.

Allegations have also surfaced against the village head of Mazan Gudu, suggesting he receives monetary incentives to comply with the miners. Although the villagers could not provide concrete evidence, his continued silence over the destruction of cattle routes and the environmental hazards in his community raises serious questions about his role and accountability.

Miners deny wrongdoing, insist operations are legal

Engineer Adamu Gerawa, site manager of Gerawa Global Engineering, said he has been in charge of the mining site for over three years and has never encountered any illegal mining activities.

According to him, all excavated sites are legally acquired from farmers in the presence of the village head, witnesses from the sellers, as well as company representatives.

He explained that the company also obtains official documentation from the local government as evidence of land purchase and approval.

Gerawa added that mining activities are carried out with the consent of community members, noting that farmers sometimes approach the company to sell their farmlands.

He further claimed to have a cordial relationship with traditional rulers in Mazan Gudu and surrounding communities, dismissing allegations of cattle route destruction.

“We pay revenue to the local government yearly. I recently paid for one year and a half. As for cattle routes, I cannot speak for other companies involved in sand mining.

But for us, we take such issues into consideration to ensure no problems arise. No one has ever complained, and I have never given money to any traditional ruler to support our activities,” he said.

Also speaking, Abdulkarim Yakubu, a laboratory technician with Cosgrove Infrastructural Limited, said the company obtained permission from the local government before commencing operations.

“We usually contact farmland owners who sell their land to us before we begin work. The areas we purchase do not involve cattle routes.

However, when such situations arise, we inform the local government authorities and only proceed after receiving approval,” he said.

When asked about measures taken to ensure cattle routes are preserved in order to prevent farmer-herder conflict, Yakubu said it was not the company’s responsibility.

Local government officials declined comment

On January 19, 2026, SolaceBase reporter visited the Gabasawa Local Government Secretariat to verify claims surrounding the sand mining activities in Mazan Gudu.

After waiting for about three hours, the reporter was attended to by the land officer, Malam Ubale, and the revenue officer, Malam Maikudi.

The officials admitted that the local government was aware of the mining activities in the community but declined to grant an interview, saying they needed clearance from the Director of Personnel Management, Hamza Lawan, who was not available at the time.

When contacted a few days later, the land officer, Malam Ubale, told the reporter that the directorate had instructed that no comments should be made on the matter.

All efforts to speak with the chairman of the local government, Pharmacist Sagir Usman, proved abortive. The reporter made attempts to meet him in person but was denied access by his aides. He also failed to respond to repeated phone calls and messages sent to him.

Village head acknowledges route destruction, denies mining-linked conflict

The Village Head of Mazan Gudu, Alhaji Yusuf Abdullahi, confirmed that at least four link roads connecting the community to neighbouring areas have been destroyed. However, he denied that the mining activities had directly caused conflict in the community.

He explained that while disputes sometimes occur, they are often linked to nomadic Fulani herders who allow their cattle to stray into farmlands and destroy crops.

“Sometimes nomadic Fulani come, and their cattle destroy farmlands. The farmers are often afraid and do not confront them directly. We usually seek the intervention of Fulani leaders to persuade them to leave peacefully,” he said.

The village head also acknowledged awareness of the mining operations in the area.

“The companies meet us after buying farmland, and we link them with the local government so they can pay the required revenue,” he stated.

State government denies authorising mining activities

Speaking on behalf of the Commissioner for Mineral Resources, Safiyanu Abba, the Public Enlightenment Officer of the ministry, Adamu Ibrahim Dabo, said the miners operating in Mazan Gudu did not seek any formal approval from the Kano State Government, despite the ministry’s regulatory role.

He stated that the ministry did not issue any permission to any of the mining companies currently operating in the community.

“We will investigate this matter, as we are hearing about it for the first time. Beyond investigation, we will invite the companies for explanation and visit the site to assess the situation ourselves,” Dabo said.

He explained that although mining licences can be issued by the Federal Government, this does not render the state ministry irrelevant.

According to him, companies are required to notify and engage the state authorities to ensure proper monitoring and compliance.

“They must come to us so we can know what is happening in our state, verify the authenticity of the licence obtained, and ensure they are properly registered,” he added.

Dabo further noted that even where approval is granted, there are established regulations guiding sand mining operations, including land reclamation and vegetation restoration after excavation.

This report was done with the support of Civic Media Lab